I Wasn’t Going to Write About This…

Spectacle, Eugenics, and Liberation in the Age of Political Theater

I wasn’t going to write about this whole RFK Jr. / Trump debacle. Honestly, I rarely weigh in on political flare-ups anymore. Not because I don’t understand politics — I do. I’ve studied history, watched cycles repeat, and lived through enough systems up close to know how power operates.

The reason I hesitate is different: I stepped away from the left some time ago. Not because I abandoned collective values, but because I could no longer ignore how often movements collapse into purity tests, infighting, and performance. Maybe I’ll return when they get their house in order. For now, I stand outside the partisan field and call myself a liberationist.

Liberationist doesn’t mean apolitical. Quite the opposite. It means I approach politics through a different lens: not as a battle of parties, but as a question of freedom versus control, dignity versus exploitation, community care versus systemic domination.

So I wasn’t going to write about this latest drama. But here’s the thing: silence is also political. And I realized I owe it to my community to share my perspective. Because what’s playing out with Trump’s “cure” spectacle is not just another headline — it’s a moment that reveals how difference, especially neurodivergence, gets manipulated in the public imagination.

And when manipulation enters the conversation about who deserves to exist, that’s when I can’t stay silent.

Spectacle as Strategy

If there’s one thing politicians understand, it’s the power of spectacle. They don’t just govern through policy — they govern through theater. The performance is the point.

This isn’t new. Ancient Rome had its bread and circuses — keep the people distracted with food and entertainment, and they won’t notice the deeper structures of exploitation. In the 20th century, authoritarian regimes mastered the art of rallies, uniforms, slogans, and staged displays of strength. The Nazi propaganda machine wasn’t just about ideology — it was about performance designed to capture imagination and control perception.

But you don’t have to look that far back. Reagan’s “War on Drugs” was staged like a blockbuster film. Families were given a slogan — “Just Say No” — while militarized policing devastated Black and brown communities. George W. Bush used the spectacle of “Weapons of Mass Destruction” to sell a war that had no basis in fact, complete with PowerPoints at the U.N. and dramatic speeches in front of banners reading “Mission Accomplished.” Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign branded “Hope” and “Change” like consumer products — a spectacle of inspiration that stirred hearts but often failed to materialize in concrete transformation.

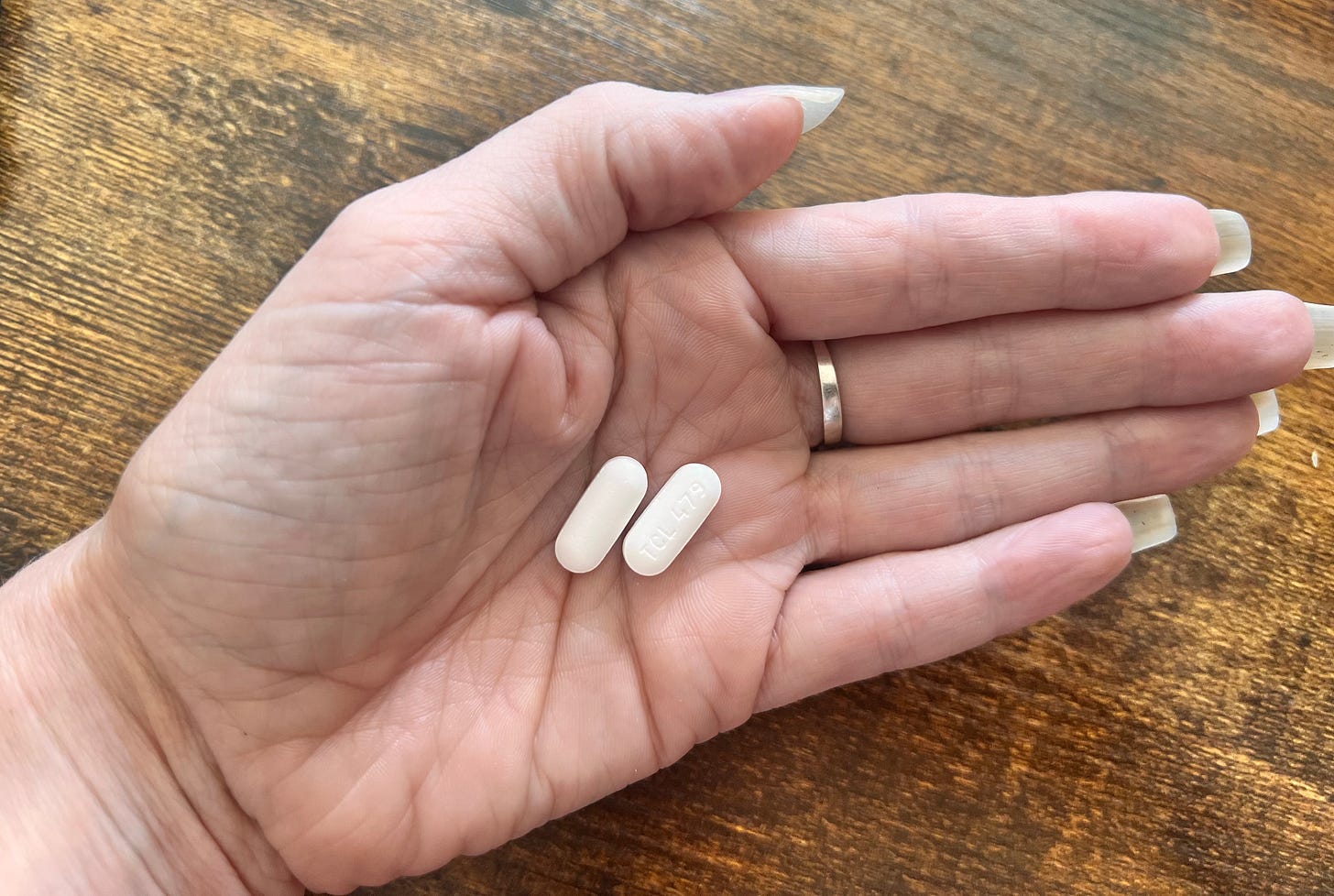

And Trump? He takes it further. His whole political identity is pure theater — rallies that mimic sporting events, catchphrases that function like slogans from reality TV, and endless stunts designed to make headlines. The recent Tylenol performance wasn’t about medicine. It was a calculated show, preying on families who are desperate for relief, dangling “cure” rhetoric as bait.

This is the essence of narcissistic politics: manipulation, not leadership. I don’t use the word “narcissist” to pathologize — I know many who carry trauma that shapes them similarly, and they deserve compassion. But in Trump’s case, narcissism is weaponized. The need to dominate attention, to perform authority, to manipulate perception — these aren’t side effects, they are the governing strategy.

From a liberationist lens, spectacle is dangerous because it disguises exploitation as hope. It blurs the line between truth and theater, between power and care. Once we confuse spectacle for safety, we are primed to accept policies that strip freedom in the name of salvation.

That’s why this matters. It’s not just about one promise or one debacle. It’s about an ancient strategy refined for the modern media age: dazzle the people, distract them with a show, then use their hunger for hope against them.

Spectacle by itself is manipulative, but paired with the politics of cure, it becomes something far more dangerous. It isn’t just distraction anymore — it’s an attempt to redefine who deserves to exist. When politicians put on a show about “fixing” divergence, they’re not just angling for votes. They’re invoking a long, violent history: the history of eugenics.

Eugenics in Disguise

The idea of “curing” difference has always been bound up with control. When Trump (or RFK Jr., or any politician) speaks of divergence as a medical error to be corrected, they are drawing from a lineage that stretches back over a century.

In Nazi Germany, the Aktion T4 program targeted disabled people for elimination, under the guise of “mercy killings.” Hans Asperger himself argued that only certain autistic children had value — those who could be molded into productive tools for the state. The rest were expendable. That logic set the stage for genocide.

But eugenics was not a uniquely German phenomenon. In the United States, eugenics programs sterilized over 60,000 people during the early and mid-20th century — often poor, disabled, immigrants, or people of color. The infamous 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell upheld the forced sterilization of Carrie Buck, institutionalized for being “feebleminded.” Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes chillingly declared: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” That ruling was never formally overturned, and its shadow lingers.

Meanwhile, psychiatry and psychology built their own frameworks around “normalcy.” The DSM emerged as a taxonomy of deviation, designed less to understand people and more to sort them into categories manageable by institutions. Difference became disorder. Disorder became disease. And disease, of course, needed treatment or elimination.

During the Cold War, conformity itself became a national security issue. To deviate in thought, behavior, or appearance was to risk suspicion. Schools, workplaces, and even family life were reshaped around surveillance and adjustment. The push for sameness wasn’t just cultural — it was political, tied to the maintenance of order.

And running alongside all of this was an expanding medical-industrial complex. The idea of “cure” has always been profitable. Every new diagnosis generates new markets — for drugs, therapies, technologies, even entire industries. Pharma companies thrive on “lifelong treatment,” while governments fund research not for liberation, but for control. A society that sees neurodivergence as a pathology becomes a society where human difference can be mined, monetized, and managed.

That’s the backdrop against which today’s cure rhetoric lands. When Trump parades a bottle of Tylenol as a symbol of medical salvation, it isn’t random. It’s tapping into a cultural script that equates divergence with disease — and disease with something marketable, treatable, eradicable. It’s a performance staged not only for political power but also for profit.

This is why liberationists name it for what it is: eugenics in disguise.

And while I understand the desperate hope of caretakers who long for relief — the exhaustion is real, the love is real — this is not the hope they’re being offered. What’s being dangled before them is not liberation but erasure. Their longing is being weaponized against them, while their despair becomes someone else’s revenue stream.

From a liberationist perspective, the danger isn’t just the rhetoric itself. It’s the way rhetoric translates into law, into funding, into policy. Research agendas are reoriented. Budgets are rewritten. Medical frameworks calcify around the idea of fixing people rather than supporting them. And once again, spectacle becomes strategy, and strategy becomes the machinery of exclusion.

The Tylenol stunt may have looked absurd to some. But in context, it was deadly serious. It was a signal. The message was simple: difference will only be tolerated if it can be managed, corrected, or erased.

That’s not hope. That’s fascism.

Internalized Scripts and False Accusations

Whenever autistic people name our strengths — our capacity for deep pattern recognition, our resistance to authority, our refusal to conform for conformity’s sake — we risk being accused of “aspie supremacy.”

The term itself has a history. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a small cluster of online communities did lean into superiority narratives. They positioned themselves as “more evolved,” “more intelligent,” even “better” than both neurotypicals and other autistics. It was a defensive posture — many of those individuals had been traumatized, ridiculed, and ostracized. Supremacy became a shield. But it was also harmful, and it left a lasting mark.

Now, decades later, the residue of that history is used against us. When we point out that authoritarian systems fear our strengths — our ability to spot inconsistencies, to resist control, to think differently — it is often misread as arrogance. The accusation of “aspie supremacy” gets hurled like a weapon, shutting down curiosity before it can even begin.

But here’s the thing: to say that neurodivergent strengths threaten authoritarianism is not supremacy. It’s analysis. History shows us again and again that systems of power target those who cannot be easily controlled. From disabled people murdered in Aktion T4, to neurodivergent kids institutionalized in mid-20th century America, to the ongoing cure rhetoric of today — the throughline is not our arrogance. It is their fear.

So why do some autistics turn on each other, deploying supremacy language against their own? Ignacio Martín-Baró, the founder of liberation psychology, helps us see this clearly. He argued that oppression doesn’t just operate through external violence but through internalized scripts — ways the oppressed adopt the worldview of the oppressor, turning that logic against themselves and their communities. In his words, domination “colonizes the mind” until we begin to police each other in the very ways power wants us to.

A liberationist lens reads these supremacy accusations in that light: as internalized neuronormativity — the scripts of control speaking through us. Many have absorbed the belief that autistic people cannot claim strength without becoming dangerous. They’ve learned to police their own community, mistaking self-recognition for superiority.

It’s a scarcity mindset, too. In a world where resources and supports are so limited, acknowledging strengths can feel like a threat to those who’ve been taught that the only valid claim to care is through weakness. And so strength is called supremacy, curiosity is called arrogance, and our voices are turned against us.

But this is not liberation. This is internalized oppression — exactly what Martín-Baró warned against.

From a liberationist perspective, the task is not to silence each other with accusations, but to hold the complexity: yes, supremacy exists and must be named when it shows up. But so must the reality that our divergences carry strengths that unsettle authoritarian systems. Naming that truth is not supremacy — it’s survival.

Liberation as an Alternative

If spectacle manipulates us, and eugenics seeks to erase us, and internalized scripts pit us against each other — what’s left? What does resistance look like when both the system and parts of our own community have been colonized by the same narratives?

For me, this is where liberation comes in. Liberation is not about left or right. It’s not about winning debates or correcting timelines. Liberation is about refusing to let systems of control define who we are or what our lives are worth.

To be liberationist means recognizing that human difference is not a defect to be managed but an ecology to be respected. Autism, ADHD, giftedness, disability — these are not separate disorders stacked awkwardly inside of us. They are interwoven patterns of cognition, embodiment, and perception. They are living ecosystems. They shape and reshape one another.

Authoritarianism thrives on sameness. It demands conformity, obedience, and predictability. Neurodivergence disrupts that. Our communication patterns resist scripts. Our cognition resists binaries. Our very existence resists the reduction of humanity into categories that can be ranked, measured, and controlled.

And that resistance is not supremacy. It’s survival. It’s diversity doing what diversity has always done: expanding the possibilities of life.

But liberation is not only about resisting. It’s also about building. It asks: how do we create spaces where difference is not only tolerated but celebrated? How do we make communities where autistic pattern-recognition, ADHD dynamism, disabled ingenuity, gifted intensity — all of it — is treated as resource, not liability?

That’s the opposite of cure rhetoric. Cure says: you must change to be valuable. Liberation says: you are valuable, therefore the world must change.

This is the shift that matters. Because if we don’t make it, we risk being seduced by the false hope of spectacle, divided by internalized scripts, and swallowed by the machinery of eugenics. But if we do make it — if we hold to liberation — then difference becomes a site of strength, creativity, and collective survival.

And that is the future worth fighting for.

Closing Reflections

I wasn’t going to write about this. And maybe part of me still wishes I hadn’t. Because these conversations are heavy, and the weight of history is real. But I also know silence can become complicity, and so here we are.

What I’ve tried to trace here is not just a critique of Trump, RFK Jr., or the latest political theater. It’s a pattern — one that stretches back through empires, fascist regimes, psychiatric frameworks, and the machinery of eugenics. A pattern that shows how spectacle, cure, and control so often work together.

And it’s also a pattern of resistance. Every time someone names their divergence as strength, every time we build spaces of belonging outside the gaze of institutions, every time we refuse to collapse into scarcity and internalized scripts — we disrupt that pattern of control. We remind each other that another story is possible.

I don’t pretend to have the final word here. Liberation is not a destination but an ongoing practice — of unlearning, of imagining, of refusing easy scripts. It asks us to sit with paradox: that difference can be both difficult and beautiful, that hope can be both necessary and dangerous, that our survival depends not on cure but on community.

So I’ll leave it here, with no neat bow. Just an invitation: notice the spectacle. Remember the history. Hold tight to one another. And keep asking — not “how do we cure difference?” but “how do we live together in ways that honor it?”

© 2025 Sher Griffin. All rights reserved.

The Cognitive Ecology Model, Synpraxis, and Exclusion Feedback Synpraxis are original works developed through years of research, writing, and lived experience. Please cite appropriately when referencing.

For permissions, collaborations, or questions, contact: sher@thecompassioncollective.earth

Thanks Sher. I hear you and will adopt the term liberationist to describe the place I find myself in, a former leftie. I appreciate the historic perspective and the need to speak up when the spectacle involves defining who must be cured as in changed. "Liberation is about refusing to let systems of control define who we are or what our lives are worth."

Brilliant. Liberationist. Thank you