In Shakespeare’s Shadow: I Learn How to Be

A Reflection on Autistic Self-Discovery, Shakespeare’s Influence, and the Journey to Authentic Being

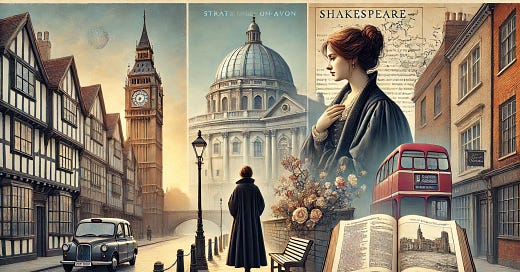

When I think back to my college years, one trip stands out as both a dream and a disaster—an experience as layered and complex as the Shakespearean works that led me to England in the first place. It was a trip I had longed for, a pilgrimage to the home of my literary obsession: Shakespeare, whose words felt like a secret language only I could fully understand. I know now that my relationship with those words went deeper than just admiration. Shakespeare’s stories were woven with a sense of systems thinking, a structure that mirrored the way my mind processed the world. In hindsight, I see that this was the first sign of a deeper truth I didn’t yet know—I was autistic.

At the time, I didn’t know why I felt such a profound connection to Shakespeare’s work. I only knew that his prose felt like home, a place where the world made sense. While other students took on the trip as an exciting academic adventure, for me it was something else entirely—it was a place where I thought I might, finally, find myself reflected. After all, Hamlet’s famous question, “To be, or not to be,” was something I had wrestled with since I could remember. It wasn’t just an existential question; it was the central theme of my life. How to be? How to exist in a world that never seemed to understand me?

What I understand now, after years of reflection, is that my connection to Shakespeare wasn’t just about his language—it was about his mind. Shakespeare thought in systems. His plays are intricate networks of relationships and consequences, where the actions of one character ripple outward, influencing everything and everyone. He saw human lives as part of a larger, interconnected whole. This is the essence of systems thinking, and it’s how I’ve always processed the world—whether I realized it or not.

For someone like me, someone who would later come to understand that they were autistic, this way of thinking felt natural. My mind always worked in patterns, seeking to understand the world through structures and connections, looking beyond isolated events to see how they fit into the larger whole. Shakespeare’s plays mirrored that complexity. His stories weren’t just isolated moments of human emotion or action; they were webs of cause and effect, where every choice led to an inevitable outcome, and every character was shaped by the systems they lived in.

Take Othello, for example—my favorite play, and for good reason. On the surface, it’s a tragedy about jealousy, race, and manipulation. But beneath that, it’s a study of systems—of inclusion and othering, of power dynamics, and of how love and identity exist within these forces. Othello’s downfall isn’t just the result of his personal insecurities or Iago’s cunning manipulation; it’s the product of a larger system, one that isolates, marginalizes, and ultimately destroys him. Othello is both a man of power and a man profoundly “othered” by the society he serves. His race sets him apart, even as his military prowess elevates him within that same system.

The tragedy of Othello isn’t just about his personal flaws; it’s about the systemic forces at play—the way society builds him up only to pull him down. Othello’s love for Desdemona, his desire to belong, and his vulnerability to jealousy all unfold against the backdrop of a world that subtly and not-so-subtly reminds him that he will never fully belong. This system, which isolates and marginalizes him, makes him ripe for Iago’s manipulation, but it also dictates his fate long before his final act of despair. He is a man caught in the web of societal exclusion and internalized doubt, a man who crumbles under the weight of systemic othering.

For someone like me, who has often felt like an outsider—who has struggled to fit into social structures that seem designed to exclude—this story was more than just a play. It was an anthem. The systems of exclusion and othering that Othello faces are the same ones I have spent my life trying to understand. They are the same forces that have dictated how I navigate the world, how I interpret social cues, how I find my place—or fail to find it—within systems that don’t always make room for difference.

Shakespeare, whether consciously or not, captured this reality with remarkable clarity. He didn’t just write about individual characters in isolation; he wrote about how those characters were shaped, influenced, and often undone by the systems around them. In Othello, love, identity, and power are not abstract concepts—they are deeply tied to the systemic forces of race, jealousy, and exclusion. Watching that play, I saw in Othello’s downfall not just a personal tragedy, but the tragedy of anyone who has been marginalized by a system that sees them as “other.”

This kind of systemic thinking—the ability to see how individuals are shaped by the structures they exist within—resonated with me on a level I didn’t fully understand at the time. Shakespeare’s plays mirrored my own way of seeing the world. The way he explored power dynamics, inclusion, and exclusion, and how each character was connected to these broader systems, felt familiar to me. It was the same way I processed my own experiences: not as isolated events, but as part of a larger pattern, a web of cause and effect that shaped my sense of self and place in the world.

I’ve spent much of my life navigating systems that were not built with me in mind, much like Othello. As an autistic person, I often found myself outside of social norms, constantly trying to figure out the rules of a world that felt foreign to me. Othello’s struggle to belong, to find security and acceptance within a world that ultimately rejected him, echoed my own journey. His story reflected not just the personal pain of being “othered,” but the systemic forces that create and perpetuate that otherness.

For me, Shakespeare was more than a master of language; he was a systems thinker. He understood that human experience is not just about individual choices, but about the structures we live within—structures of power, love, race, and identity. He understood that our lives are shaped by forces beyond our control, and that understanding those forces is key to understanding ourselves.

In hindsight, I see that my deep connection to Shakespeare’s works, and particularly to Othello, was one of the first signs of a deeper truth about myself that I didn’t yet have the words for: I was autistic. My mind naturally grasped the patterns, the systems, the webs of connection that Shakespeare wove into his plays. While others might have seen Othello as a straightforward tale of personal jealousy and downfall, I saw the broader system at work—the forces of exclusion, marginalization, and the power dynamics that dictated Othello’s fate. It was this systemic thinking, this ability to see the interconnectedness of everything, that made Shakespeare’s works feel like home to me. And in a world where I often felt out of place, that was no small thing.

This way of seeing the world resonated deeply with me, though I didn’t have the words for it at the time. I just knew that Shakespeare’s works made sense in a way that the rest of the world didn’t. His language, too, was full of layers—gestalt-like in the way it formed whole meanings from fragmented pieces. Metaphors and imagery interconnected, creating a tapestry of understanding that felt so aligned with how my own mind processed reality. Shakespeare saw the world in terms of these systems, and that was exactly how I experienced it, even if I didn’t yet know that my way of thinking was different from others.

When I was a child, my ability to memorize literature was both my refuge and my curse. I would recite Dr. Seuss at age three, Shakespeare by the time I was ten. To most, it seemed like a quirky party trick—a talent that set me apart but never quite brought me closer to others. The more I absorbed words, the more isolated I felt. I could understand Shakespeare’s themes of betrayal, love, and power, but I couldn’t understand the everyday social interactions around me. I could not articulate why they confused me, and no one else seemed to notice my disorientation. This disconnect, this constant state of being misunderstood, became the thread that tied so many of my life experiences together.

That trip to England was supposed to be a kind of escape, a magical alignment of my inner world with the outer one. My mother, ever the champion of my passions, made sure I could go, despite our financial struggles. We were of the lower socioeconomic reality, but she never wanted me to miss an opportunity to chase something I loved. And I did love Shakespeare—his words were the only consistent way I could make sense of the world’s chaos. But I hadn’t yet learned that the structure in Shakespeare’s stories couldn’t protect me from the unpredictability of real life.

I arrived in England with a heart full of hope, but quickly realized I was out of my depth. My peers, all from more privileged backgrounds, didn’t think twice about taxis or expensive meals, while I tried to stretch $100 over two weeks. My parents had paid for the trip itself, but everything extra was my responsibility. I wanted to belong, to blend in, so I mimicked their behaviors, ordering meals without looking at the prices, hopping into cabs, and pretending I could keep up. But after just three days, my reality hit me. I didn’t have enough money for a museum entry fee, much less a sense of security. When a professor suggested I call home and ask for more money, I felt a wave of shame. How could I explain that we didn’t have extra?

So, I called my mom, and she wired me $200—money I knew she could barely spare. “Budget carefully,” she said gently. And I did, in the only way I knew how. I skipped breakfasts, pilfering crackers and fruit from the hotel, and ate Burger King chicken nuggets for lunch, alone, while the others dined at quaint restaurants. But it was more than just budgeting money. I began to budget my energy, my emotions. Every interaction became a calculation—how much masking, how much pretending, could I afford today?

And then there was Richard III at the Queen’s Theatre. It was a performance I had been waiting for my whole life, or so it felt. We walked through Piccadilly Circus on the way there, the lights and the architecture overwhelming and beautiful in equal measure. I was trying to take it all in, but my mind was splintered—trying to absorb the enormity of the city while keeping track of my spending, my belongings, my emotions. I was trying to keep everything in check, just as I had learned to do all my life.

When the performance began, it felt like the world paused. Shakespeare’s words filled the air, and for a brief moment, I was transported. I felt understood, if only by a distant voice from centuries past. I allowed myself to feel the rush of excitement, to lean into the beauty of the moment. At intermission, my professor offered to buy me a drink, and I politely declined. I reached into my purse, intending to grab some change for a small soda. But my hand met nothing. My wallet was gone. So was my passport. Everything. I froze, the world crashing back into focus with a cruel clarity. I had been robbed in the very city that was supposed to be my sanctuary.

I didn’t say anything. Not to my professor, not to anyone. I sat back down, dissociating for the rest of the performance. The second half of Richard III was lost on me, but I was too ashamed to speak up, too overwhelmed by the idea of explaining my situation to anyone. For the rest of the trip, I withdrew, quietly stepping out of group activities and opting for solitude instead. I wandered the streets of London alone, with only $40 left in my coat pocket. There was a strange comfort in that isolation, though. I didn’t have to mask, didn’t have to pretend. For the first time, I stopped trying to fit in with my peers. I allowed myself to exist in the way I had always wanted—in my own world, at my own pace.

I wandered through neighborhoods both pristine and gritty, absorbing the city in a way no guided tour could offer. I found solace in the public buildings, in libraries and coffee shops, in the quiet spaces where I could simply sit and observe. I walked to Abbey Road, not for the photo op that others sought, but for the quiet reverence of being alone with a piece of history. These were moments of clarity, moments where I didn’t feel like an outsider looking in. I was simply me, an observer in a world too loud and too complex, but still beautiful in its own way.

Stratford-Upon-Avon was my sanctuary. While the other students filled their time with tourist activities, I found joy in the simplicity of the place. I helped the bed-and-breakfast owners with chores in exchange for lunches and endless cups of tea. I drank tea until it felt like it was a part of me. And every evening, I watched Shakespeare’s plays, allowing myself to be transported into the stories that had always made me feel understood. I didn’t need to take the guided tour of Shakespeare’s house—I knew that just being there, in his presence, was enough.

The other students whispered about me, their laughter trailing behind me as I walked alone, but I no longer cared. In that small town, in the quiet spaces I carved out for myself, I realized something that would take me years to fully understand: I didn’t need their approval. I had always been searching for belonging in the wrong places, outside of myself. Shakespeare’s words had shown me that I wasn’t alone in feeling “other,” but what I hadn’t realized was that my sense of self-worth wasn’t tied to fitting in.

Years later, after my autism diagnosis, it all made sense. The constant feeling of being out of sync, the way I understood things others didn’t, and the way I struggled to communicate my understanding. I had spent years masking, pretending, trying to fit into a world that was too overwhelming, too loud, too chaotic. But in the quiet moments of that trip, I stopped pretending. And that was when I began to find myself.

Even now, I look back at that trip as a turning point. It was a disaster in many ways—a loss of money, friends, and comfort. But it was also magical. It was the moment I stopped trying to be what I thought I should be, and started exploring who I truly was. I didn’t fully understand it then, but England became a place where I could begin to exist on my own terms, without the pressure of belonging to anyone else’s narrative.

What I didn’t understand at the time, standing in the shadow of Shakespeare’s words, was that self-acceptance is not a destination you arrive at once and for all. It’s a practice, a continual process of choosing to be—over and over again. Sometimes you choose it consciously, and other times it chooses you, quietly unfolding in the spaces between the noise, when you’re too tired to pretend anymore.

But the truth is, that wasn’t the last time I would feel lost, nor the last time I would find myself again. Over the next 25 years, I would lose and find myself countless times, each experience peeling back another layer of who I thought I was, revealing parts of myself I hadn’t yet understood.

That trip to England marked the beginning of a cycle—of gaining clarity, then losing it again, of constructing a sense of self only for it to be torn down by life’s unpredictability. Each time I rebuilt, it was with more understanding, more awareness of the invisible forces that shaped me. Each time I felt lost, I returned to the question posed by Hamlet: To be or not to be—to hide or to live authentically.

In the years that followed, I would confront new challenges, new versions of the same struggle I had faced on that trip—trying to belong in a world that often felt too chaotic, too indifferent. I would lose myself to the expectations of others, to the pressures of masking, to the exhaustion of trying to fit into places that didn’t make room for me. But just as I lost myself, I would find myself again, often in the quiet moments of solitude or in the words of a book, much like I had in England.

I’ve learned that this is the nature of life—of my life, especially. There will always be moments of being lost, of feeling unmoored. But there will also always be moments of clarity, where I see myself clearly, in all my complexity. And I have come to realize that this cycle of losing and finding is not a failure, but a necessary part of the journey. Each time I lose myself, I return with a deeper understanding, a little more self-compassion, and a clearer sense of who I am.

England was just the beginning of that journey for me, but its lessons echo across the years. I didn’t need the souvenirs, the guided tours, or the approval of others. What I needed was to be with myself, to allow my own company to be enough. And maybe that’s why I still return to Shakespeare, even now—because his words remind me of a truth I’ve been living all along: that to be lost is not the end. It’s simply the place where the next chapter begins.

“Had always been searching for belonging in the wrong places, outside of myself.” Truly the most important detail and often the most difficult to find. Thank you again for sharing your perspective and insight!