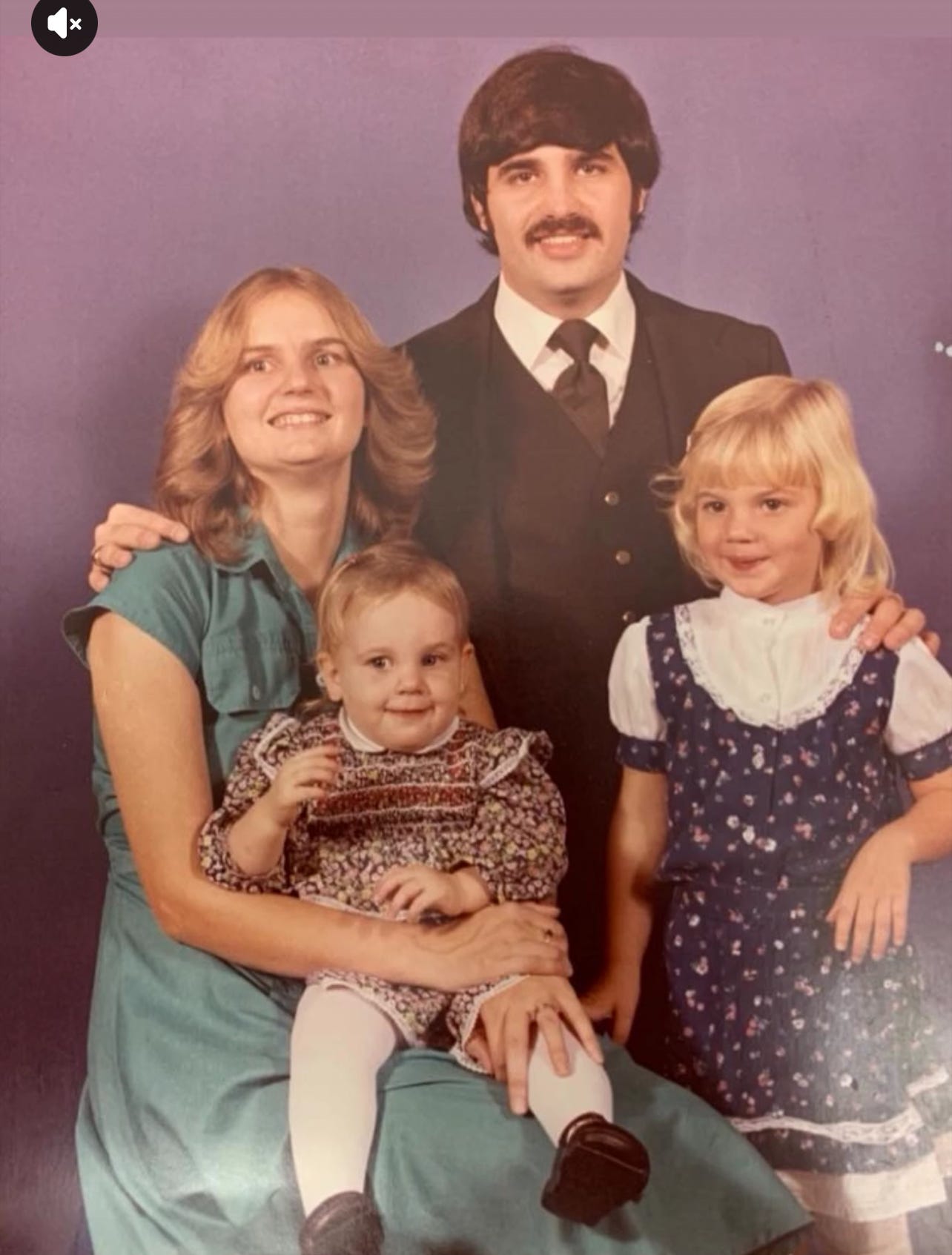

This is me, my sister, my mom, and my dad—around 1981.

My younger sister hadn’t been born yet.

We didn’t know, then, how much we’d carry.When I look at this photo now, I don’t just see childhood.

I see the systems we were inside of—Christianity, whiteness, silence, survival.

I see love trying to speak through inherited patterns.I see a beginning.

Not of clarity—but of rupture.This is the family I began in.

This is the life that gave rise to the questions I now walk with.

This is why the bridge matters.I didn’t know it then, but this photo holds the questions that would one day shape my life.

Who am I beneath the systems I inherited?

What does it mean to belong—to a family, to a people, to a world that doesn’t always recognize your whole self?

What does it mean to remember?

The Bridge Is Not a Metaphor

I’ve crossed the bridge over and over again.

Not just between ideas, but between histories, between bodies, between ways of knowing.

This isn’t a metaphor.

This is a place I live.

Each crossing brings something different. Each return teaches me something my bones knew before I had words for it. I used to think this was a kind of failure—this looping, this re-entering. Now I understand: it’s a way of listening. A way of healing. A way of becoming human again.

This is not a flex.

It’s a function.

It’s a role—and I take it seriously.

I wasn’t raised fully inside my Indigenous lineage, but it lives in me.

It shapes the way I move through complexity.

It shows up in my grief, in my silence, in my refusal to abandon nuance in favor of clarity.

I am not a Christian. I am not Indigenous in the way institutions require for legibility.

I am an Integrationist—a weaver, a meaning-maker, someone who sits at the threshold and learns to speak across spiritual and cultural frequencies without collapsing difference into sameness.

This is my bridge work.

Not to translate.

Not to teach.

But to tend.

Discomfort Is Not What You Think

We are often told that “discomfort is necessary for change.”

And it’s true—but not in the way people usually mean.

Colonial systems—religious, academic, political—taught us to mistake confusion for danger. To treat disorientation as moral failure. To collapse at the first sign of tension.

This is not fragility.

It’s not weakness.

It’s a patterned nervous system response, shaped by generations of dominance, disembodiment, and disconnection.

I was trained to defer to authority instead of insight. To argue instead of feel.

To call avoidance “resilience.” To name performance as power.

And yet—even in that disconnection—something deeper kept reaching.

Discomfort, I’ve learned, is not a wall.

It’s a threshold.

It’s not what breaks us—it’s what invites us into another way of knowing, if we’re willing to stay long enough to listen.

Listening Across Lineages

Some truths cannot be translated.

And they shouldn’t have to be.

When people say, “I don’t get it,” in response to Black or Indigenous truth-telling, they often mean:

“This is not being presented in a way that I’m used to.”

But that doesn’t make it less true.

It means we’ve been trained to only recognize truth when it’s delivered in the language of dominance, rationalism, or white legibility.

I don’t believe Black and Brown thinkers should soften their voices, slow down their grief, or tailor their wisdom to our comprehension.

That is not their role.

The labor of unpatterning the listener belongs elsewhere.

That’s where the bridge comes in.

That’s where I come in.

As an Integrationist, I hold space between traditions—not to make them compatible, but to honor their friction.

To let them speak across, not through, each other.

And to let those who are listening find their own way to resonance without demanding coherence.

Composting the Inheritance

I inherited a colonized mind.

One that mistrusted dreams. One that pathologized grief.

One that wanted to flatten everything into logic—even my own body.

But underneath that was something older. Something rooted.

Something Indigenous.

And I don’t mean that as identity performance.

I mean that as relational memory—ancestral, ecological, and cellular.

Coloniality didn’t just extract land. It tried to sever meaning from rhythm, person from people, story from soil.

Uncolonizing for me isn’t about rejecting what I inherited.

It’s about composting it. Turning it. Layer by layer.

Until I can feel the root system again—beneath the concrete.

My ancestral knowing isn’t always legible to others.

It shows up in how I sit with silence.

How I slow down when everyone else speeds up.

How I refuse the binary of “either/or” and choose instead to stay with “both/and/and still becoming.”

This photo was taken around 1975. My mother stands here with her family—her three brothers, two sisters, and both of her parents. Of the eight people in this photo, only two are still alive.

I don’t include this image to romanticize the past or to fix it in place. I include it to remember. To name that what I carry didn’t begin with me. That even if I wasn’t given every story, every ceremony, or every explanation, something deeper was passed on—through silence, through gesture, through survival.

My bridge work isn’t abstract. It’s embodied. It’s inherited. And sometimes, it’s very lonely. But looking at this photo, I’m reminded that I’m not doing this work alone. Even those who are no longer living are walking with me.

Some of them never had the language for what I’m writing now. But I believe they felt it. I believe they lived the tension I’m now trying to name. This is the ground I stand on—not perfection, but presence. Not purity, but connection.

Bridge Work as Devotional Practice

Let me be clear: I’m not neutral. I’m not detached. I’m not performing coherence.

This isn’t an identity.

It’s a devotional practice.

Bridge work, for me, is about refusing erasure without demanding legibility.

It’s about moving with respect through Indigenous knowledge systems, Christian mysticism, somatics, poetry, and ecological memory—without trying to flatten them into one belief.

I hold space for those walking toward discomfort.

I hold complexity when others try to simplify.

I refuse to rush the process of becoming just to prove I’m “on the right side.”

Not because I’m better.

Because I’ve lived the rupture.

Because I know what it means to lose meaning—and what it takes to reclaim it.

I’m not here to be a translator.

I’m here to practice presence in the space between.

Walking Backwards into the Future

I used to think healing was about arriving at clarity.

Now I know it’s about becoming coherent.

Not in thought—but in relationship.

In rhythm. In land. In lineage.

My ancestors don’t ask me to be pure.

They ask me to remember.

To walk with care. To honor the tensions I carry.

White supremacy didn’t just colonize land or culture.

It colonized listening. It colonized time.

It taught us to hear urgency as virtue, and depth as threat.

But I’m unlearning that.

I am walking backwards into the future—carrying only what I’m ready to grow.

I’m listening differently now.

Not for the loudest answer—but for the softest truth.

So if you’re reading this and something stirs—something uneasy, something unspoken—don’t turn away from it.

Follow it.

Ask yourself:

What was I taught to forget?

What stories are buried in my bones?

What truths still live inside my silence?

You don’t need to be fluent to begin.

You don’t need to be ready to arrive.

You just need to be present.

The rest will come.

I stand with you in in the presence of the space between the no longer and the not yet remaining calm so to let the truths alive within surface